Terrorism, Extremism, & Memes: An Exploitation

Pepe the Frog, who has become something of a mascot for far-right online circles

(December 23rd 2019)

Whilst using the internet in the modern day it is borderline impossible to avoid being flashed with countless mocking satirical images, sometimes about politics, sometimes about popular culture, sometimes about society itself. These fine artistic creations are known commonly as “memes”. For those who are new to the 21st century, welcome to the internet, I'll be your guide.

Memes are a relatively new genre of humour however they have spread exponentially given the worlds rapid increase in usage and reliance on the internet. The high-speed development and obsessive use of social media such as Facebook and Twitter has greatly helped ingrain memes into the fabric of online humour as it is today.

Memes can be silly and fluffy. In the beginning memes were commonly witty and humorous such as “Socially Awkward Penguin”, whilst around 90% of memes centred around around cat photos. Nowadays many memes are ridiculous, banal, and just outright nonsensical... and proud of it. Political memes are widespread and have grown significantly since Donald Trump became US President and throughout his term. The worlds most powerful man himself has also frequently communicated through the medium of memes via Twitter. Evidently, memes have an enormous worldwide reach especially as humour is universal and in some ways they have become the language of social, cultural and political commentary for the internet.

A vintage dank 10/10 savage meme

However, even memes are not free from exploitation, as in recent years they have become something of an encouraging, coaxing recruitment tool for online far-right extremists in order to subtly influence people into their radical political world and to subtly encourage terrorist attacks, partly by glorifying previous attackers who share similar beliefs, partly by spreading provocative propaganda through the unusual but attractive medium of childish humour. An example of this is Pepe the Frog, a previously innocent meme who, after being hi-jacked and appropriated by right-wing circles, became something of a mascot for the online far-right.

Far-right appropriation of Pepe the Frog, portraying him as a Jew content with 9/11

Of course, this has become more of a problem since the astronomical popularity of social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, therefore these memes can reach a far wider audience than previously. The wider and more burning problem however comes from other sites such as 4Chan, 8Chan (although this was taken down in the wake of the El Paso massacre), and to a lesser extent Gab as these places are largely unregulated and unmoderated, therefore users can post almost anything they want, regardless of how inflammatory, provocative or misinformed it is. These forums and websites can also help to create a smaller but dedicated sub-community of people who help give a legacy to attackers, and who spread propaganda and misinformation that sways people into a far-right extremist leaning, some of whom go on to carry out literal attacks.

The methods carried out by online users of these sub-communities (intentional or not) is different from other, more well known, kinds of encouraging terrorism. Although it doesn't target specific people one-on-one, such as how several jihadist preachers target those incarcerated in jail, and whilst it doesn't openly encourage people to carry out attacks, these memes can easily reach a wide audience across the world (owing to its attractiveness because of its humour which can be shared worldwide) and by doing this, they can aid to influence people to agree with and support their political standpoint.

The Influence & Attraction Of Humour

Over the years, numerous attackers have shown a significant interest in memes or meme culture and some have shown their political beliefs online in meme form on social media. A non-exhaustive list of those who appeared well-engrossed in the world of far-right political memes are Christchurch mosque gunman Brenton Tarrant, Poway synagogue shooter John Earnest, Halle gunman Stephen Balliet, and failed Baerum (Norway) mosque attacker Philip Manshaus.

By far the most notorious and infamous terrorist amongst these communities is “Saint” Brenton Tarrant, “The Shitposting Terrorist” whose armed assaults on two Christchurch (New Zealand) mosques left 51 dead and scores injured. Before, during, and after his twin attacks Tarrant created a string of online meme-related references and inspirations. From blaring “Serbia Strong”, a Serbia political song more commonly known as “Remove Kebab” that references war-criminal Radovan Karadzic, to giving “O.K.” hand-gestures (something that some believe to be a subtle inclination to “White Power” in court), Tarrant left a host of references to the online far-right subculture community. Tarrant even referenced YouTube celebrity PewDiePie before his attack in order to gain maximum exposure and attention online by tapping into the Swedish Youtubers enormous online popularity. At the time of the attack, Pewdiepie was long embroiled in a well-known battle with Indian channel T-Series in an effort to become the first YouTuber to reach 100,000,000 subscribers. Tarrant referenced memes directly and unreservedly in his manifesto that he made public before his assaults on two mosques in the New Zealand city of Christchurch. Within his writing “The Great Replacement” (itself named after an online far-right conspiracy theory regarding Jewish control of world affairs) he wrote to his online community “... do your part by spreading my message, making memes and shitposting as you usually do.”, and noted its appeal to potential new right-wingers, saying “Whilst we may use edgy humour and memes in the vanguard stage and to attract a young audience, eventually we will need to show the reality of our thoughts”.

In the coming months after the Christchurch assault, various other attackers (or attempted attackers) showed significant connections to the online subculture world, and who also showed a significant degree of inspiration taken from Tarrant, some of whom showed their support or beliefs in meme form, some of whom referenced memes directly. Poway (California) attacker John Earnest, a 19 year old who carried out an anti-Semitic attack inside a synagogue, posted online shortly before opening fire. Within this post, he compiled a soundtrack of what he deemed to be “very meme-able songs” and insisted “Meme magic is real.” towards the end of his post. In return, he was called “based” and told to “get the high score”.

John Earnests online post shortly befort opening fire in a Poway synagogue

Given their short text and often recognisable context, this means that memes can become internationally popular, and aren't held back entirely by any language barriers. In Norway, the attempted (and failed) Baerum mosque shooter is alleged to have posted on a Chan forum (although 8Chan was removed shortly before in the wake of the El Paso massacre) showing support for Tarrant, Crusius, and Earnest in the form of a “Chad and Stacy” meme, glorifying and praising the trios prior efforts in their attacks.

A Legacy Created

Asides from trying to radicalise potential attackers through propaganda and rhetoric, this online subculture can also act to canonise and glorify previous attackers. In turn, this can be inviting to aspiring attackers who are seeking this (often posthumous) sanctification and legacy-building. The creation and mass-spreading of memes centred around an attacker can help to solidify them as something of a celebrity around far-right online communities, and this can help to build a legacy for them for years after their death.

One of the most notorious examples of posthumous glorification is that of Elliot Rodger, the British-born Isla Vista gunman who plotted extensively to shoot up a California sorority house, leaving extensive material behind such as videos and an excessively long self-written manifesto.

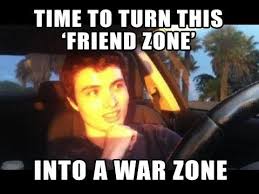

Elliot Rodger, the "Supreme Gentleman", glorified in meme form

Rodger plotted to gain revenge on women he felt had rejected him, and although his spree efforts ultimately failed (he failed to enter the front door of the sorority house, and only 2 of the 6 fatalities in his assault were actually female) this has not stopped him becoming sanctified amongst far-right online communities. Now commonly referred to as Elliot “The Supreme Gentleman” Rodger, his attack itself served to inspire the Toronto truck attack in April 2018 carried out by a perpetrator who is believed to have frequented 4Chan (a place where Rodger is somewhat famous). The Toronto attacker himself, Alek Minassian, was also glorified in song.

"Egg White"s song "Alek Minassian", created from the viewpoint of the Toronto incel terrorist inspired by Elliot Rodger

Online far-right communities such as the Chan series (under whichever incarnation) can offer something of a martyrdom and a legacy to potential attackers. This online sanctification can achieve to make them famous within these communities where they can leave a legacy and be remembered for years even after death. Although an attacker may not achieve world-wide notoriety, for some attackers this legacy-making within such a hardcore community can be an additional highly appealing incentive to carry out an assault.