Explaining ISIS Lack Of Success In Europe Recently

October 18th 2019

This article largely uses data from the Terrorism Situation & Trend Report (TE-SAT), all of which are available here: https://www.europol.europa.eu/activities-services/main-reports/eu-terrorism-situation-and-trend-report#fndtn-tabs-0-bottom-2 .

Europe has been rocked by Islamic jihadist attacks in the past decade and Islamic State (IS) have inevitably been at the forefront of such assaults. The casualty figures, both fatal and non-fatal, makes for depressing reading across the continent. However, these numbers have shown a significant decline over recent years.

According to data from the Terrorism Situation & Trend Report (TE-SAT, which covers the European Union, not Europe as an entire continent) in 2015 there were seven completed jihadist attacks, leading to 150 deaths, all of which were in France except for two in Copenhagen. In 2016 there was 10 completed attacks, leading to 135 deaths. Unlike the year previously this was not confined almost entirely to one nation, as assaults in France, Belgium, and Germany showed the problem to be far more widespread geographically. In 2017 Europe suffered ten Islamist attacks although the number of fatalities dropped significantly to 62. By 2018 these numbers dropped even further, as despite seven completed attacks being carried out this lead to just 13 fatalities. It is difficult to give an exact number for the current year of 2019 as (1) the year is not complete and (2) attacks are still being investigated to determine whether or not they were inspired by jihadism and if any links to Islamic State can be found. The Limburg truck ramming in October was at first believed to be terror-related, however recently this assertion appears to have been largely reconsidered by German authorities. So far this year (as of October 15th) an estimated 8 people have been killed by Islamic jihadism. Although this is still 8 too many this shows a consistent and significant drop in fatality numbers each year since IS efforts peaked in 2015.

Evidently this portrays a steep decline in Islamic State successes in carrying out jihadist attacks against Europe, a place where they have consistently attacked and repeatedly called for public attacks, whether these are carried out by IS soldiers themselves or by sympathisers and/or supporters. There are several reasons that may explain why the groups success in the continent has significantly declined.

European Exodus

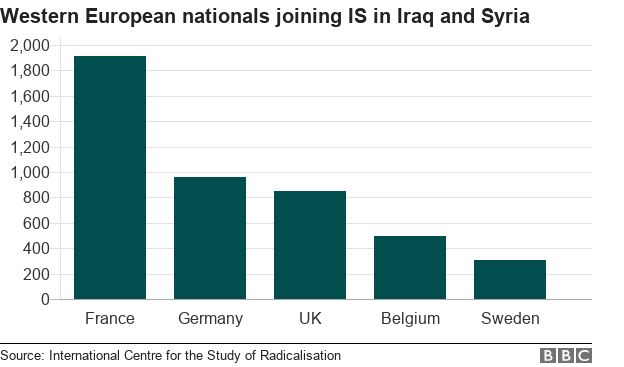

One plus point (at least for Europe) to Islamic States attempts at building a caliphate in Iraq and Syria is that this encouraged many aspiring jihadists to leave the continent in order to fight with the group in the Middle East. TE-SAT data (page 40 of their 2019-released report covering the year 2018) estimates that approximately 5,000 ISIS sympathisers have left the European Union to join groups in Iraq and Syria, with nations such as Belgium, France, Germany and the UK being the most departed from. Circa 900 British citizens are believed to have left the island to fight for Islamic State abroad. By the end of 2018, they estimate, less than 2,000 appeared to still be in the region (TESAT, report for 2018, p40), many of whom will have been injured, in hiding, unable to afford a route back home, or will have taken residence in a neighbouring country. Furthermore, they estimate around 1,000 will likely have been killed, presumably either by their own terrorist attacks, fighting, natural causes, poor living conditions within their area, or killed by foreign intervention such as extensive bombing campaigns against the group.

Many European IS supporters who left for the Middle East will have become stateless as their national governments revoked their passport. In the UK, around 150 Brits who left to fight for IS have had their passports and citizenship revoked, most notably Shamima Begum, who left Bethnel Green with two friends to support the group aged just 15, and Jack Letts, who had the British side of his British-Canadian dual citizenship rescinded.

Whilst US President Donald Trump insisted ISIS Euro-ex-pats should be captured and taken home to face justice within their home country, few nations are interested in the concept of having known radicalised and trained jihadist returning to their society. Public opinion in France, for example, shows that 89% of respondents are against the return of adult jihadists to their country. No country except Germany appears interested in the return of foreign jihadis, explains an Iraqi researcher. Indeed, this would likely need to be a collective agreement from all European Union nations as a jihadist returning to Belgium would have free movement therefore would pose a threat across large parts of the continent.

The Caliphate Is Gone

ISIS officially declared their caliphate in June 2014 and through extensive ground movements they slowly began to take pockets of land across Iraq and Syria. At its peak their caliphate covered as much as one third of Iraq and Syria. Its leaders held strong ambitions for a true Islamic State across the Middle East and under the motto “Baqiya wa tatamaddad” (“remaining and expanding”) they aspired to take Iraqi and Syrian land before expanding further across the Middle East and then the world.

The caliphate was not just geographical territory for the group to hold, train, and to expand upon, it was a major propaganda tool in recruiting domestic and foreign soldiers to join the group, as well as towards encouraging jihadist attacks across the West. The belief in the caliphate and its ambitions were a key tool for inspiring fighters and potential jihadis to become a part of a greater political and religious cause that they could contribute towards, and for many who either left Europe to fight with the group or who sympathised with them and carried out attacks in the West, this was a cause worth literally dying for. Furthermore, the group astutely insisted that Muslims were religiously obliged and duty-bound to join the caliphate. The only alternative to migrating to join the caliphate in Iraq and Syria, they insisted, was to perpetrate a terrorist attack within their own country. To decline to do so would make them an apostate.

Since then however, ISIS have gradually lost their caliphate over the years. After an extensive series of anti-ISIS campaigns such as foreign airstrikes and groundwork movements by groups such as the Syrian Democratic Forces the ISIS caliphate was eroded and eventually deteriorated. On March 23rd 2019, ISIS lost the Syrian village of Baghouz, losing their last piece of territory of their now-former caliphate.

Although ISIS still exist across the world (one offshoot is taking up residence in West Africa) and whilst attacks are still being carried out in their name across the West (such as the Lyon bakery bombing) the caliphate is no longer a reasonable propaganda tool for the group to utilise to encourage attacks. There is now no caliphate worth fighting for, let alone dying for.

Increased National Security

In the wake of numerous large-scale attacks such as those on the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris in 2015, and the Paris attacks of November that year, national security spending increased greatly across the West.

After the Charlie Hebdo attack France vowed to maintain around 7,500 military jobs that were previously due to be cut. French then-President Francois Hollande also raised the terror threat level to its highest level and mobilised around 10,000 troops across the nation in order to protect potential terrorist targets such as schools, newspaper offices, and houses of worship. The nation also raised counter-terrorism spending throughout the next four years by around 3.8billion Euros, and increase from the current expenditure of 31.4billion Euros.

The January and November attacks in Paris did not only lead to changes in counter-terrorism expenditure and efforts in France, as various nations throughout Europe made significant changes in response. UK chancellor George Osborne promised to spend an extra £3.4bn on counter-terrorism efforts as a result of the November attacks. Included in this was around 1,900 extra security and intelligence staff, as well as doubling funds for aviation security (in light of the suspected bombing of a Russian plane over Egypt the month prior). This was the largest increase in UK security spending since the 7/7 bombings of July 2005.

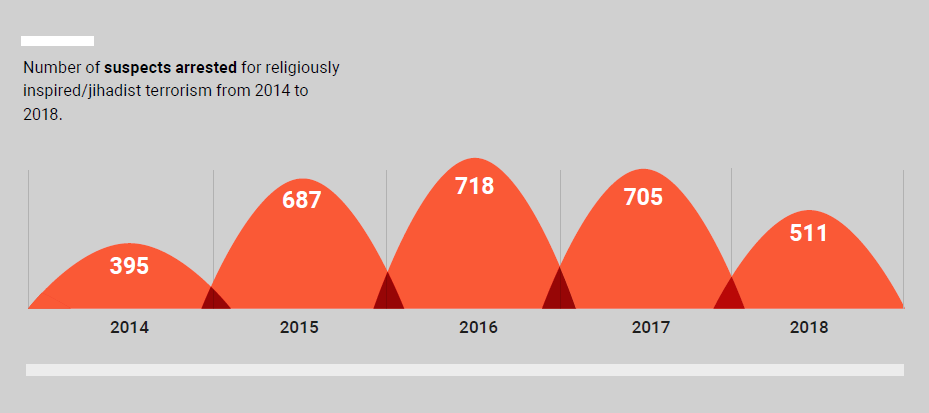

In conjunction with this, TE-SAT reports also show an increase in thwarted terror attempts over the following years, rising from 11 in 2017, up significantly to 16 in 2018. TE-SAT figures also show heightened efforts in apprehending potential jihadists or those culpable of jihadist activity with terror-related offences rising significantly over the following years, hitting a peak of 718 in the year 2016.

Source: TE-SAT report released 2019 (covering year 2018), page 29.

ISIS increased their efforts throughout the continent and were admittedly highly successful in many of their completed attack. However, this was countered by authorities increased levels of determination to meet this new jihadist threat as well as a strong and lengthy willingness to back up these counter-terrorism efforts financially.

No Notoriety

Terrorist groups thrive off the fear and terror they engulf a society in. They need to be seen as a fearsome and notorious group worth joining and worth dying for. The massive amounts of money that nations spent on countering the threat of ISIS was a signal of how powerful they were believed to be. Images of post-attack catastrophes and of people running for their lives sent a message that they were fearsome worldwide. Casualty numbers showed unflinchingly the destruction the group was capable of.

Since then, this has changed significantly, as Islamic States level of devastation caused and their casualty numbers have decreased significantly. Islamic State or their supporters have not carried out a terrorist attack killing more than five people since the Barcelona vehicle attack in August 2017, whilst the deadliest and perhaps highest-grade attack since then came in December 2018 during a shooting at a Christmas market in Strasbourg (France) which killed exactly five people. Attacks in the year of 2019 have arguably been lower grade, bar a shooting on a tram in Utrecht that killed four, and a stabbing by a police intelligence worker, also killing four. On at least four occasions they have failed to take a life, three of which resulted in a minor casualty toll (Oslo, Conde-Sur-Sarthe, Milan). This is a significant recession from massive wide-scale co-ordinated attacks such as those carried out in Paris 2015 and Brussels 2016.

This could perhaps be explained by increased arrests over terror offences due to heightened surveillance, leading to cells being broken up or apprehended in full, meaning large co-ordinated attacks are failing to come to fruition. In 2018, all completed jihadist attacks were carried out by lone-wolf attackers, and so far in 2019 this trend appears to be continuing. A jihadist attack in Europe carried out by more than one perpetrator has not occurred since the London Bridge attack of June 2017.

The group has also resorted to claiming responsibility for attacks they did not commit in order to garner attention and to keep themselves in the limelight (such as Las Vegas or the Danforth shooting), however the spotlight they receive from this is likely to be diminished due to it self-undermining their own credibility. Other stories such as that of ISIS fighters being trampled by wild boar, as well as failed attacks in New York in December 2017 and Brussels in June 2017 have helped to erode the groups fearsome reputation in the West even further. Not only does this highlight to potential jihadis that attacks will not always be successful, nor will they definitely be high-fatality, it shows that although ISIS are still a serious threat to Europe, they are becoming less and less a group worth dying for. In December 2015, Tashfeen Malik (one half of the husband and wife duo who carried out a deadly mass-shooting in San Bernardino, California) insisted she “wanted to be a part of it”, writing a month after the Paris attacks which killed 138. Recent attacks by the group however, appear to do little to inspire future recruits to give their lives for the cause. Although she was writing from a standpoint regarding ISIS trying to recruit disabled fighters, Chelsea Daymon appropriately summarised the situation: “From a recruitment standpoint, no one wants to join a losing battle.”.

Losing My Jihad

A significant part of jihadist martyrdom is believed to be that one must die during their attack, such as being killed by the state (police, the death penalty, etc), or by the attack itself (such as a bomb blast). In many recent terrorist attacks this goal has not been achieved by the perpetrator, including several higher profile assaults such as the New York truck attack of October 2017 or the failed New York bombing of December that year. Of the seven jihadist attacks that occurred in 2018, the perpetrator survived in three of them, whilst in 2019 (so far as of October) the perpetrators have failed to achieve martyrdom in all but one of the eight (*this number may of course change) attacks so far (in the Paris police stabbing attack).

US President Donald Trump called defiantly for the death penalty for Islamic jihadists after the New York truck attack in October 2017 however this is far more likely to work in favour of the attacker given many are likely to hold an ultimate goal of death through martyrdom. To guarantee the death penalty is essentially to guarantee martyrdom through state execution, almost as if to say that if one doesn't complete your martyrdom in the attack the state will do it for you.

It could be argued that a better alternative would be for attackers to suffer the indignity of life imprisonment, and with no chance of parole they shall die behind bars, not through martyrdom.

Conclusion

Europe is absolutely in no way “safe” of Islamic State extremism. Although the group has been battered over the previous years whether through airstrikes in Iraq and Syria or by increased intelligence operations across each nations, the group still remains to be a household name and terror threat levels still rightly remain high. However, given the scale of efforts against the group both in the air and on the ground this is not without due effects and results. One of the groups biggest recruitment propaganda tools, the caliphate, has disintegrated and vanished. Terrorist plots are being thwarted due to increased operations and expenditure within the field, and this in turn leads to fewer high-fatality attacks that inspire other jihadis to follow suit. Their notoriety is waning due to their lack of success, whilst many of those capable of carrying out a devastating attack have found themselves stateless and in limbo having fought abroad.

Europe is not safe from Islamic State, and likely will not be for decades to come, however the terrorist group has found itself beleaguered, battered, lost, and desperate not just across the continent but even in its own now-former-caliphate in Iraq and Syria. Europe is not home and dry, but Islamic State in the modern day is struggling to hit first base.